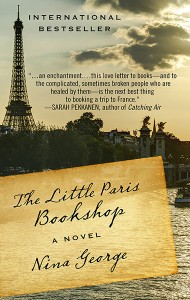

I had the opportunity to interview Nina George, the author of the popular novels The Little Paris Bookshop and Das Lavendelzimmer. Here are some highlights.

Do you write for others because you have to write or for yourself only?

I write so as to better understand what I think, to see the world more clearly—and because it’s how I express my desire to create, to change the world, my love of humanity. Writing for me is a way to communicate in every direction: with myself and also with other people. I also translate the dark depths of the human experience into stories so that others can learn something—tolerance and how to see themselves more clearly.

Writing is an art form that people do not go looking for. Writing seeks out its practitioners. This doesn’t mean that genius is everything. What matters is whether one can stand not to write or to communicate with this medium. I could never give up writing. If I did, I’d cease to exist. I think, breathe, live and write. It’s all the same thing. The loss of one would mean that I’m dead.

How many days do you actually write, and how rigid you are about that schedule?

Every single day. For the past 25 years. Writing comes from writing, not from waiting for it to happen.

While writing, what kind of relationship do you often form with your own writing self – a painful or a joyful one?

It depends. Thinking about a story is very enjoyable, and for a novel this process can easily take a year. The agony begins when I start writing the first sentence. And it doesn’t end at least until several months after the book is published!

The best, most intensive and also the longest period before I begin actually writing a novel comes after I “fall in love” and carve out the main theme. This is when I get to know the characters. Each one of them, including the secondary characters, has a role to play within the entire cast—and an inner motivation that mirrors the main theme. The theme of Das Traumbuch (Book Of Dreams: Germany, March 17th 2016) poses this question: “Is there such a thing as a right life that we can choose day after day—or can the wrong path also make us happy?” Each character reflects the theme in their own way. For this to happen, I have to know them well. Each one gets their own biography in my mind, and I run each one through my own life’s experiences nearly on a daily basis. How would X react if, like me, he was stood up by his tango partner? What would Y do if someone jostled him at the bakery, just like they did me? I am the stand-in for a powerful cast of characters, and I put myself in the skin of each one until it feels right, the person’s psychology is believable and they become a meaningful addition to the cast. It is very important, I believe, to place the relationships between the characters on a solid foundation. Also, I want to know how they express themselves, how they talk to others, how they react to each other, the ways in which they misunderstand and unsettle each other.

Once I’ve completed this process—which can take six months, sometimes even a year—I start plotting. I always begin at the end. Invariably, I know how things turn out. And what each character has to have gone through in order to grow, to move beyond themselves and learn something from life.

I don’t focus on the details until the end—and even here, I spend less time on analysis and focus more on emotional development. Until I find the voice, pacing, rhythm, sound and temperature of the story. At times, I write the same scenes over and over again for three months until I’ve found the texture of the novel that I’ve sensed ever since I first “fell in love” with it.

During these moments, I cry a lot. I despair, start over again, want to change careers, yell at my husband. I hate the world. I hate myself. And yet I know that the more miserable I feel, the more it will all pay off in the end.

How do you recognize if you are on the wrong track?

I get into a terrible mood and feel like lashing out at everyone. Or I can’t figure out what should happen next. When this happens, I go back page by page to see where I took a wrong turn. Sometimes, I throw it all out and start over. Usually, this is in the “first draft” stage, the first three months of the “writing phase.”

Do you feel you and the characters in your books have always been well understood by your readers?

My readers don’t have to understand them. It’s not a test. A book is a work of art that comes alive only in the reader’s head. To feel understood, all I have to do is tell the story as best I can and inspire the reader to draw associations. It is my job to serve the story and the reader, not the other way round. Rather than the reader understanding me, I must be able to help the reader create his own work of art in his head. I do this through fresh yet fitting metaphors, through precise descriptions of emotions and psyche and by making my characters believable. They are true to life only when they’re as boneheaded as we are; they captivate us only when they venture to do things we wish we dared to do ourselves.

Do you lose yourself in your writing? The very fact that writing is a very lonely art, do you sometimes feel lonely?

I often feel alone, but it’s not because of the writing. Writing is a very social, communal process! After all, in order to write about people, their thoughts, feelings and fears, I have to get close to them in a very trusting and intimate way.

And I don’t lose myself in the writing, I find myself there.

My writing follows several phases: flow and revision. When I’m “in the flow,” I let loose inside and follow the story. When I’m revising, I switch gears and apply craft quite rationally. I look for repeated words, for pacing and the rhythm of the language. I check dialog to make sure it’s something people actually say. I conduct research and read the work aloud.

These two processes—flow and revision as well as editing—are independent activities. Revising my work during the early writing phase would destroy the flow, while losing myself in the revisions would unravel the story.

I do not tolerate any disruption when I’m in the deep writing phase, in my “Pensieve” a world outside the physical world. During this time, I hate to have anyone look at me. Or talk to me. Or breathe in the same room with me. However, this period lasts for only three or four months. Afterwards, I’m perfectly social again.

What books are currently on your book stand?

Schmerz (Pain) by Zeruya Schalev

Das finstere Tal (The Dark Valley) by Thomas Willmann:

Das Buch des Theseus (The Book of Theseus)

Don Winslow

What books are you embarrassed not to have read yet?

Everyone.

What do you plan to read next?

One of the manuscripts I’m blurbing: An extraordinary book called The Summer Guest by Alison Anderson. It pays tribute to Chekhov.

Which books might we be surprised to find on your shelves?

You will find every single book by Mister Stephen King and Mr. Koontz. I am also in love with George R. R. Martin. In the 80s, when I was a teenager, I (gasp!) adored Jackie Collins and Eric van Lustbader.

I own around 3,000 books. Some of them reflect certain periods of my life. Others were only for research.

What is next for Nina George and what would be next for Nina George if the sky were the limit?

I address a highly existential theme in Das Traumbuch: Life consists of a sum of hourly decisions. Which of them are the right ones? Which bring us happiness, love, friendship and which lead to loneliness and despair? Publisher Eddie, war correspondent Henri and Sam, a highly sensitive teenager, grapple with these existential questions when Henri falls into a coma after an accident.

I tell the story from the first person points of view of completely different people. Edwinna, who goes by the name Eddie, publishes magical realism with a special sense of the miraculous. Sam is a highly gifted 13-year-old, who sees sounds as colors and who experiences people, places and moods more intensively than others do. Henri, the former war correspondent is Eddie’s ex-lover and Sam’s father. He lay dead for eight minutes following an accident and is now struggling to wake up from a coma. He has a message to deliver to those he loves from the place where he very nearly was lost.

In Das Traumbuch, I write about the unknown realms between life and death, between reality and dreams—and also about the brief moments when doors open onto entirely different paths in life. The ones we don’t trust ourselves to take.

If the sky were the limit, I’d love to write a book about two girls born of the same surrogate mother. One daughter remains with the mother and the other is sold to a wealthy couple in the United States. Neither twin knows about the other until one day they meet by chance in an airport restroom in Paris and switch lives…

Don’t we all dream that a completely different life exists somewhere out there, just waiting for us to come and start living it?

Interview response translation by Heidi Holzer; Featured photo: Urban Zintel © by Nina George

- Visit www.nina-george.com

- Purchase Nina’s books at Amazon.com

Tags: Author, Authors, Book Reviews, Interview, Interviews, Nina George, The Little Paris Bookshop

Posted in Book Reviews, Reviews |

Leave a Reply